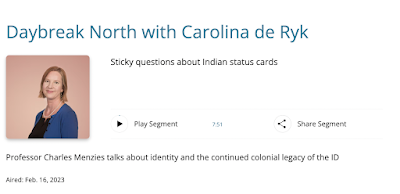

On air interview, Thursday, February 16, 2023.

Link to CBC audio clip.

[00:00:25.010] - Carolina

The all native basketball tournament is underway right now in Prince Rupert. But as we found out on yesterday's show, one young woman is being kept off of the court. 19 year old Stacy Edinger is not allowed to play for the old Massett women's team due to her status card number being connected to another village. This in spite of familial ties to Old Massett. Here's her coach, Len Arns, speaking yesterday on the program.

[00:00:51.940] - Len

It seems very unfair, especially for us to be under the status cards when our alaskan brothers don't have status cards. The Nisga don't have status cards, they have membership cards. That doesn't make them any less. It's a card issued by the Canadian government that shows us that this is our Indian number. We're not a name where number that's.

[00:01:18.900] - Carolina

Old Massett basketball coach Len Arns. Now, on the surface, status cards are a form of government issued ID, but their effect on people's lives can be much more significant. I'm joined with more by Charles Menzies, who's a professor at the University of British Columbia and a member of the Gitxaala First Nation. Good morning to you.

[00:01:38.110] - Charles

Good morning. And if you don't mind saying a shout out to all the people up there playing basketball, I wish I could be there in the stand watching it, or maybe one day I'll join the Masters team and play on the court again.

[00:01:49.140] - Carolina

Now, that would be wonderful to see. Charles, I'm sorry that you weren't here to be watching the games, but as you heard, some controversy this year over the idea of status cards, what does a status card represent to you?

[00:02:03.110] - Charles

That's a tough one because it's a recognition of where we're from and all that, but it's also an act of the government as part of a colonial legacy that brands indigenous people as being separate from the rest of society. Yet it also comes with a whole bunch of other recognitions of the government that actually owes us because of the historical legacy. So it's really conflicting and problematic. And of course, sometimes people, when you use the card in a place that you need to, sometimes they respond positively, sometimes they don't respond at all. Sometimes they're just pains in the backside about it.

[00:02:43.300] - Carolina

What's been your experience with using a status card?

[00:02:46.870] - Charles

Well, I think one time I tried to use it to vote in a provincial election. I remember actually going into the Dunbar Community Center and using the card for it, and then the fuss and things. They called somebody over to look at it. Then another person came over and back and forth. After a while, you see there that the line is getting longer and longer and longer, and everyone's kind of staring at you, staring at the card, looking at it, talking to each other. Finally, I just gave up and gave them my driver's license.

[00:03:14.230] - Carolina

And what was that like?

[00:03:16.190] - Charles

It was really unsettling. I didn't actually appreciate just how I'd feel about it. I was really taking aback. But I'll tell you, I haven't used it again for voting in the provincial elections.

[00:03:28.310] - Carolina

And why is that?

[00:03:30.690] - Charles

Because the trouble and the sort of whole nonsense to go through with that process, it's really it's kind of like you think, well, this is a low cost thing to do, but it's the emotional turmoil for doing it. I'll be quite honest, I was quite surprised. But it did remind me of a story my dad told about going to me about trying to get his glasses down here in the lower mainland. And he went into a store and he picked out his glasses and his frames and stuff like that. And then the optometrist said, okay, so how are you going to pay for this? And dad took out his status card, and the guy looked at him and goes, oh, no. And he reached below the countertop, pulled out a box, about half a dozen black frame plastic glasses. You choose one of these. My dad says, there's just no way I'm doing that. And so it's that kind of response to the way these things, how people respond? And I think the Union of BC Indian Chiefs did a study a while ago after the grandfather and his granddaughter were arrested and handcuffed at a bank in downtown Vancouver.

[00:04:38.520] - Charles

They did a study, and about 99% of the people they interviewed experienced some form of discrimination and prejudice for trying to use the card, which is a legal right to be able to use the card.

[00:04:51.340] - Carolina

I recall that report. It came out last fall from the Union of BC Indian Chiefs. But there's another part to this story, too, because in our history, and not very distant history, there were periods where status was withheld or stripped from certain people. So what are the consequences of not having a status number?

[00:05:13.380] - Charles

It gets really complicated back and forth. But one of the difficulties, too, is the whole realm of identity fraud that builds up and around these categories as well. When people I mean, the University of British Columbia just went through a situation with a fairly prominent individual who it turned out had not been honest about who they were and where they came from or any of that. So on one level, when things, when material resources count on these things, you really need to have some kind of documentation and proof about what's going on. At the other hand, there's people whose families have been disconnected and who are, have every right, to be part of the community, but may have lost some connection. And then, of course, not having this little piece of government issued paper, it's a problem. And there is no easy solution except to say communities need to have the authority and power to make these decisions. This is the academic of me coming back saying, but there needs to be protection for minority communities within our communities who might then be disenfranchised because of underlying discrimination internally as well. So there's no good solution for a problem created by a colonial system.

[00:06:28.080] - Carolina

And so how realistic would you say it is for the system to stay the way it is, moving forward, as you say, communities are changing?

[00:06:37.200] - Charles

Yeah, well, I think one of the things it was mentioned in the clip from the Haida coach about the different types of enrollment cards in Alaska or the Nisga citizenship cards. I think we need to move to an idea of membership or citizenship, not idea of this kind of old colonial label 'status.' That at least could be a first step to move in that kind of direction. I mean, and we've only really had the cards in their current variation kind of format since the mid 1950s, even though there was an Indian registry since sometime in the 1850s or 60s.

[00:07:12.780] - Carolina

How much appetite do you think there is to make a change to the status?

[00:07:20.620] - Charles

I think everyone I talk to says there's something should be done, and then when you say, well, then what should we do? People just kind of go, well, they're not sure. And it's almost as though it's better to have something that's bad than something that we don't know what it looks like, but doesn't mean we shouldn't try. I mean, I do think it's time for a change.

[00:07:39.140] - Carolina

I really appreciate you taking the time to talk to me about it today, Charles, and I look forward to seeing you when you're next in Prince rupert.

[00:07:46.260] - Charles

The same. And again, I say a big hello to all family and friends who are up there enjoying the games. And go warriors.

[00:07:55.000] - Carolina

All right. Thanks, professor.

[00:07:56.800] - Charles

Right, bye bye.

[00:07:57.860] - Carolina

Charles Menzies, a professor at the University of British Columbia, also a member of the Gitxaala First Nation. What has your experience been like using a status card? Have you had a negative experience? Maybe you've had a positive experience? You can share your story. Email us at daybreak north at CBC CA. You can also call us on our listener line that number 1-866-340-1932.